Of all the Developer Backend-As-A-Service products from Google, if I were to ask you which one created the most paths for Indie developers to build things, Firebase Realtime Database wouldn't come at the top of that list.

But what if I were to tell you, that we wouldn't have some of the most prolific mobile and web games of our time without it? The green dot we take for granted next to our chat's names, indicating that someone is online, requires a ton of engineering and edge-case handling behind the scenes to work -- Something that Firebase Realtime Database makes effortless.

Having used Firebase Realtime Database in several of my projects to build everything from user online indicators to complex flows involving real-time chats that destruct when both users go offline, I can confidently say the product was a pathbreaker.

Me being me, as always, attempted to rebuild a basic clone of the real-time database server and that's what I'll be explaining in this post.

What we'll be looking to build and explore:

- An appropriate data structure and storage solution

- Client SDK Design and local caching

- Capability to run real-time data queries

- Capability to write data and have other listeners auto-update

- Factoring in Security Rules for data reads and writes

- Actions on disconnection

- Additional: Support for listening to values once

- Scaling up beyond a single server

You can follow along or see the final implementation for the realtime database server here: deve-sh/Realtime-Database-Server.

Some constraints to begin with

- Max permissible database size: 100 MB max (Real-life limit similar to the one imposed by Firebase Realtime Database). Remember, the database is for secondary use cases and not your primary database and hence the data structure and the data you store in it should be carefully thought out and structured.

- Max Concurrent Connections: 100 (We'll aim small for now, on the paid tier Firebase Realtime Database allows you to have 200K concurrent connections, which can be achieved by a cluster of servers)

The Tech stack we'll use

We can build a real-time database on top of any language or framework we need. One would be tempted to use powerful languages like Go to build it, and they would be right in doing so, some languages are in fact better suited to these use cases.

But looking at the security rules structure of Firebase Realtime Database gives us some insights into what language is used for its implementation or at least its rules validation service, it's JavaScript, identifiable via the === syntax for equality assertions and the fact that you can have a trailing , at the end of an expression without it causing a syntax error.

{

"rules": {

"sessions": {

"$uid": {

".read": "$uid === auth.uid",

".write": "$uid === auth.uid",

}

}

}

}So for our implementation as well, we'll use JavaScript. And since we just decided to use JavaScript for security rules, let's just use JavaScript/TypeScript throughout.

An appropriate data structure and storage solution

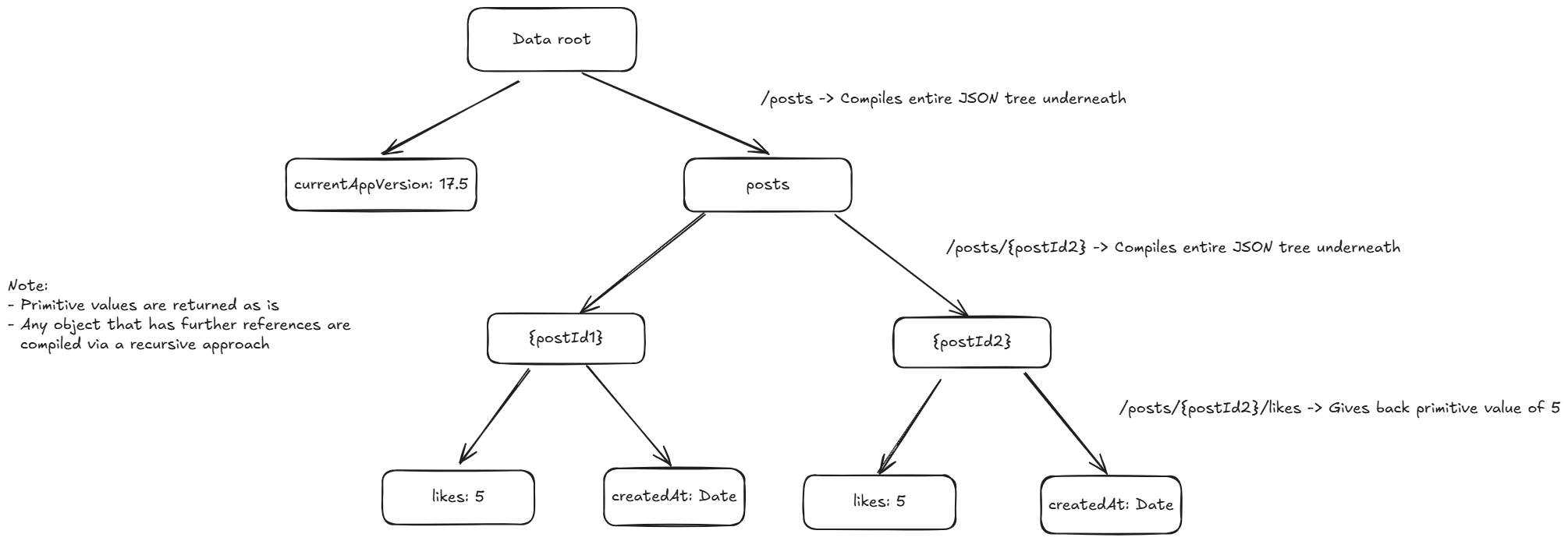

While Realtime Database might show its data as a JSON, it’s a little more complicated than that. Remember, you can read and write data to any key however deeply nested it might be.

Thus it makes sense to store the database as a Tree-structure instead where data values can be recursively iterated on and compiled into objects or primitives (numbers, boolean, null, string).

A Trie data structure is purpose-built for reading and updating such values. Although the act of ripping off an entire tree branch on replacement of a complete object might be expensive, it can still be done quickly as we don’t have to search the entire tree for a match.

A tree is also useful when you want to search for connections that are listening to a path, as a connection listening to /users/ will also be listening to /users/<uid> and /users/<uid>/lastPosition, I.E: The search operation just has to be a startsWith operation of the final path.

There are 2 choices we have regarding what we can do for data storage:

- In-memory storage

- Data storage in an external database (After all, realtime database’s orchestrator is its server, not the underlying data storage)

In-memory storage:

- Beneficial for faster reads and writes

- Limited by the amount of data we can store (Memory constraints of the machine or VM we might me running on)

- Data can be represented as plain JSON as intended from the user’s perspective or as a lazy-loading-tree as we saw above

- Security Rules are easy to implement in an in-memory JSON structure, if the top isn’t allowed, then nothing further down the tree is allowed to be read or written. Although storing the whole tree in memory has some weird repercussions.

Data Storage in an external database:

- Slightly slower reads and writes as that has to happen over a network

- No real limitation on the amount of data that can be stored and retrieved, you can shard databases as needed and with a tree structure, it’s much easier to create sharding keys on a per-database basis.

- Data cannot be stored as plain JSON as that will have to be loaded in memory each time and transported through the socket channels from the database to the server, causing memory and network overheads.

- Security Rules are easy to implement in this approach itself, if the top isn’t allowed, then nothing further down the tree is allowed to be read or written. In fact, given we can’t store everything in one variable like the in-memory approach, this is by default more secure.

Our application could support both, for smaller projects and instances, a 50MB storage limit with in-memory JSON can be provided for smaller users at the expense of scale.

For larger users, a limitless amount of storage billed per MB could be provided with even sharding of data.

We could use an SQL database or a graph/tree database which is optimized for this under-the-hood. Since all ops can run inside a VPC, they’ll also be very fast to run.

For our simple app purposes, we'll use the In-Memory tree structure, and limit the amount of data that can be stored in it. But we'll create an adapter that can then be used to extend to over-the-network database calls as well.

Laying the foundation for our Server

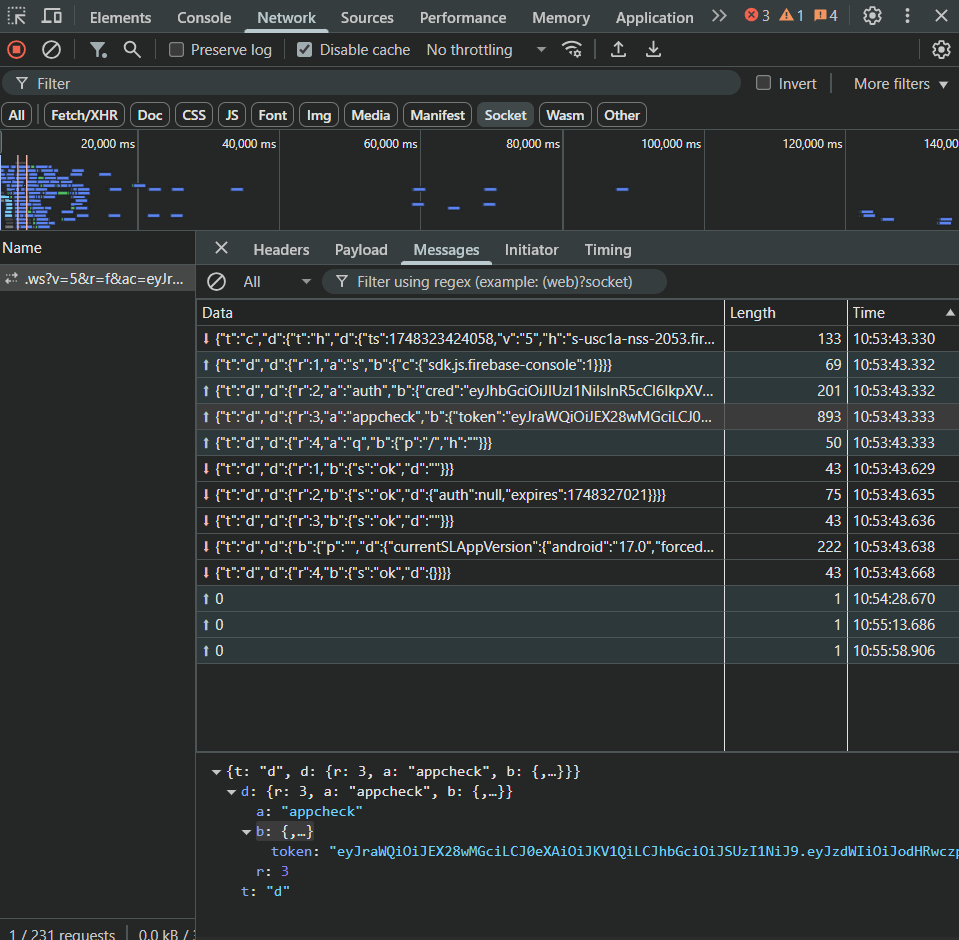

The client and server communicate over WebSockets. Messages and Auth requests are sent as socket messages with a sequence ID for the message and the server responds to it.

Thus, that’s also what we’ll use.

While WebSockets enable bi-directional communication between the client and the server, there doesn't exist a default

replymechanism. It can, however, be created very simply by using a uniquemessage_idsent from the client, and in a reply the server sends back areplied_tovalue - the same as that ofmessage_id.

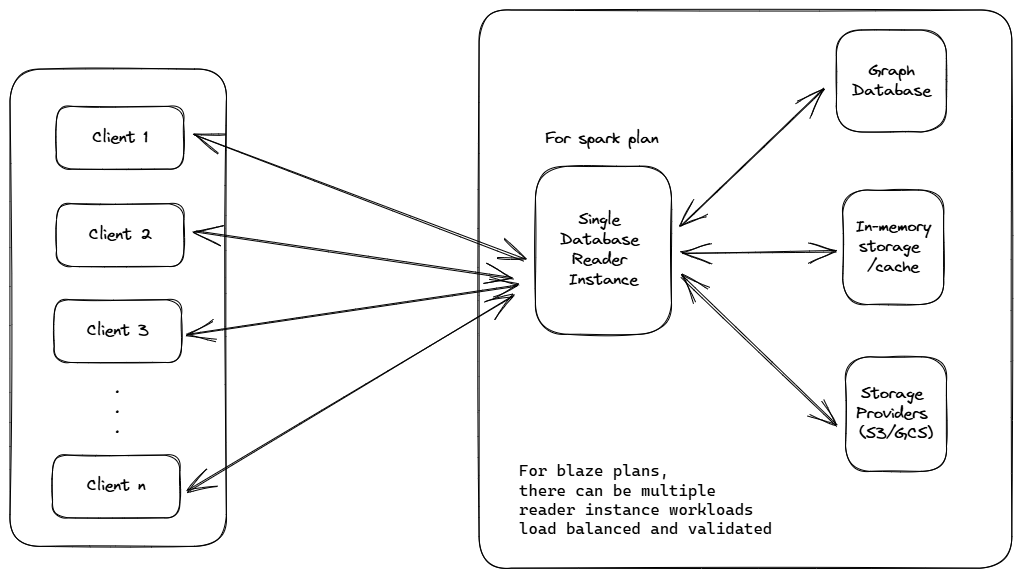

Now, coming to the architecture, for spark/free plan users, it's more than enough to have a single server instance/micro-virtual-machine on a shared core, as the resource constraints are pretty simple to implement and work with. Rejecting additional websocket connections and having a limitation on memory usage is something Docker containers are really well set to do.

For a higher scale, we will discuss this in the final sections of this post.

WebSockets and their handlers

For our purposes, we can obviously use Socket.io but where's the fun in using something that has everything mapped out for you. To go slightly deeper we'll use the ws library which only takes care of the websocket transport for you but gives you enough control to build the kind of functionality you like.

We'll structure the server in such a way that:

- There is a single manager class for all connections so it can enforce connection limits.

- There is a single data manager class with interfaces to further classes of in-memory storage or database storage depending on the tier the application is running on. So the server code just has to interact with this manager and not worry about anything else.

- Each connection will be wrapped in a class that adds functionality to it and handles common use cases such as message validation, and test mode debugging.

- Other functionality such as Security Rules will also have their own manager classes and resync periodically or on signals to ensure config changes are propagated correctly.

We'll only support JSON messages in the format specified in further sections.

Handling connection status

To ensure all connections are healthy and weed out any connections that have gone stale, we'll implement heartbeats every 15-30 seconds via the usual Socket ping-pong mechanism.

Any connection that doesn't send back a pong to our server's ping is considered to be stale/dead and automatically removed from our resource (It's disconnection handlers are run accordingly)

Registering Listeners and Disconnect actions

To register a listener on a path, the client can send a subscribe message to the server with a dataPath. The server stores this mark and uses it for propagating updates.

Additionally, whenever a client socket initializes a listener, it is usual to send back the current data on the tree path. So we'll do that.

There's also a neat concept of "disconnect actions", i.e. When a connection closes from a client, the server is supposed to perform some actions. This is relayed to the server by the client ahead of time and can be useful for performing things such as marking a User ID as offline once a disconnect happens and removes the worry of tricky cleanups that you would have to do on the client before it closes a connection or when there's just has bad network and cannot reach the server in the first place.

Listening for messages and sending back messages from our server

Let's first define the types of messages we can have from the client to the server.

// For security rules

export type SET_AUTH_CONTEXT_FOR_CONNECTION = {

type: "set_auth_context";

token: string;

};

export type SUBSCRIBE_TO_DATA = {

type: "subscribe";

dataPath: string;

};

export type UNSUBSCRIBE_TO_DATA = {

type: "unsubscribe";

dataPath: string;

};

export type CREATE_DATA = {

type: "create_data";

dataPath: string;

data: string | null | Number | Record<string, any>;

};

export type UPDATE_DATA = {

type: "update_data";

dataPath: string;

updates: string | null | Number | Record<string, any>;

};

export type DELETE_DATA = {

type: "delete_data";

dataPath: string;

};

export type WRITE_DATA = CREATE_DATA | UPDATE_DATA | DELETE_DATA;

export type SET_DISCONNECTION_HANDLER = {

type: "action_on_disconnect";

action: UPDATE_DATA | DELETE_DATA;

};

export type SOCKET_MESSAGE_FROM_CLIENT = { message_id: string } & (

| SET_AUTH_CONTEXT_FOR_CONNECTION

| SUBSCRIBE_TO_DATA

| UNSUBSCRIBE_TO_DATA

| WRITE_DATA

| SET_DISCONNECTION_HANDLER

);The listening and sending back messages part if then fairly straightforward, the ws library we decided on using provides abstractions to mount listeners for WebSocket message events and replying to them.

As stated in a section above, each message from the client SDK will have a message_id parameter, which will correspond to a replied_to parameter sent by the server to create the impression of a bi-directional dialogue between the two parties.

try {

const message = JSON.parse(data.toString()) as SOCKET_MESSAGE_FROM_CLIENT;

const isValidMessage = validateMessageFromClient(message).isValid;

if (!isValidMessage) return;

this.handleMessageFromClient(message);

} catch {

// JSON formatted messages are the only ones supported

return;

}Handling Reads and Writes + Propagation of writes to listening clients

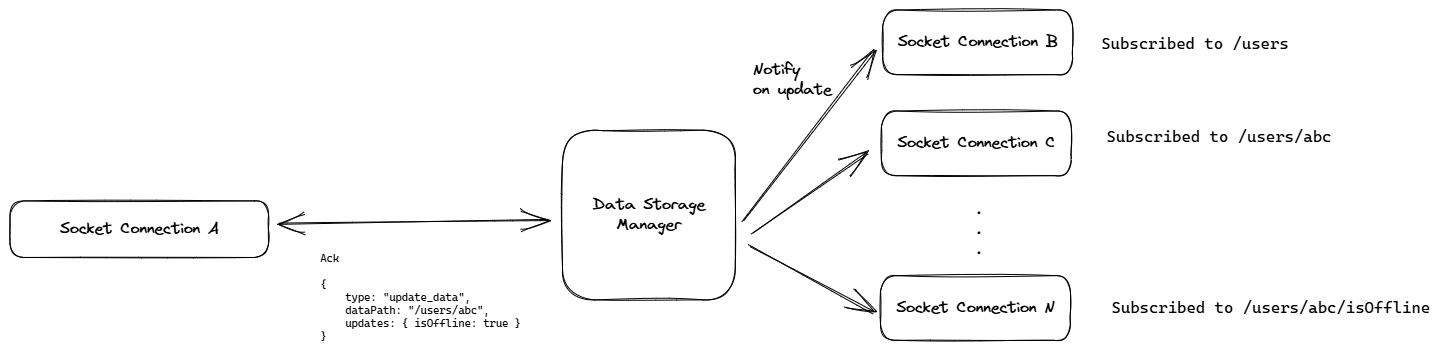

The pattern for reading and writing data is simple. Because of two of our architectural decisions:

- Since we have a common data storage manager that interfaces with our choice of in-memory storage or on-a-disk-or-database-storage, we have a single point for reads or writes happening.

- We also have a common connections list manager, which can tell us which socket connections are listening to which paths.

Thus, this culminates into a simple flow of:

- Socket Connection A sends a write request to a data path with updates/new data

- Data Storage Manager accepts the write post verifying it with security rules

- It checks for any subscribers to the path or its parent paths (The data is a JSON tree which makes this operation very convenient) and sends a message to the subscribers.

Security Rules

We'll have the same structure for our security rules as what Firebase Realtime Database has.

- Rules can be defined on a per path basis, the lack of a

.reador.writeop defaults the op tofalseand prevents reading on the entire nested tree. - Dynamic paths can be used by starting them with a

$sign, i.e:/users/$uid

export type RuleValue = boolean | string;

export type RuleNode =

| {

".read"?: RuleValue;

".write"?: RuleValue;

}

| { [key: string]: RuleNode | undefined };

export type SECURITY_RULES_SYNTAX = {

rules: {

[key: string]: RuleNode;

};

};

export default SECURITY_RULES_SYNTAX;You can see a basic implementation of the security rules mechanism here: security-rules.ts.

Client SDK Design and local caching

The Client SDK is fairly simple for Firebase Realtime Database, unlike its successor Firestore.

We'll only have the following methods to implement in our SDK:

class RTDB {

apiKey: string | null = null;

constructor(apiKey: string) {

throwIfAPIKeyIsNotPassed();

this.apiKey = apiKey;

}

ref(path: string): {

on: (event: 'change', listener: (data: Record<string, any>) => any),

off: (event: 'change') => void,

onDisconnect: ({ action: { type: 'update_data' | 'delete_data', data: Record<string, any> } }) => void,

set: (action: { type: 'create_data' | 'update_data', data: Record<string, any> }) => void,

} {

...

}

}

// Instantiate

const db = new RTDB(apiKey);

// Use

const ref = db.ref(`/users/${userId}`)

ref.on('change', (newVal) => { ... })

ref.off('change')

ref.onDisconnect({ action: {type: 'update_data', data: ... }})

ref.set({type: 'update_data', data: ... })Our client SDK can also handle caching for listening to or reading from values when the client is offline via several mechanisms. I've written at length about enabling this kind of behaviour in apps in this post.

Additional: Support for listening to values once

Firebase Realtime Database, till very recently didn't have a way to listen to values only once, the only way to listen to it once would be to set up an on('value') listener and just close the channel when the first event for the listener was triggered.

This of course was tricky to do and bug-prone when you put the usage of this method in the hands of the consumers. The SDK is now updated to include a .value() property to get the value of the database reference once.

We can do the same with any one of two simple approaches:

- On the client-side: Abstract the single-time real-time listener to the client SDK and simply unsubscribe once we receive the value. The drawback is it still creates a WebSocket channel which is costly to start up in the first place.

- Combination of the backend and the frontend: Simply expose a REST API endpoint for values which the client SDK can invoke to get the required value. This skips the part of having to setup a realtime WebSocket channel, and is hence much more efficient and much less bug-prone.

Scaling up beyond a single server

All the above is great for a basic user operating on the spark/free plan, where the constraints are very well defined.

But what if a game someone built on your system suddenly goes viral and they need more capacity? What do we do for someone who upgrades their plan and wants unlimited storage and infinite connections? Well, this isn't a new problem to solve and has been solved by countless companies for countless use cases before with varying nuances.

To achieve unlimited storage and infinite connections, regardless of the

Database: We can't go with an in-memory store, obviously. Our bet will be on a database that supports sharding to split load across several database instances if required.

Since JSON is a tree-structure, it naturally allows for sharding of data based on an a sharding key. The tricky part will be defining the right sharding key to avoid the problem of "hotspotting" where some shards are populated heavier than other shards due to the natural nature of data being inconsistently scattered.

The Server: This is where things get slightly tricky. We have to scale up and down regardless, but as these servers have client WebSockets connected with them, it gets tricky to balance connections and ensure they don't get disconnected when you scale down + Ensure a client.

- Use sticky connections from clients to ensure one client doesn't connect to more than one server.

- Have a database proxy to manage connections with these servers to the database.

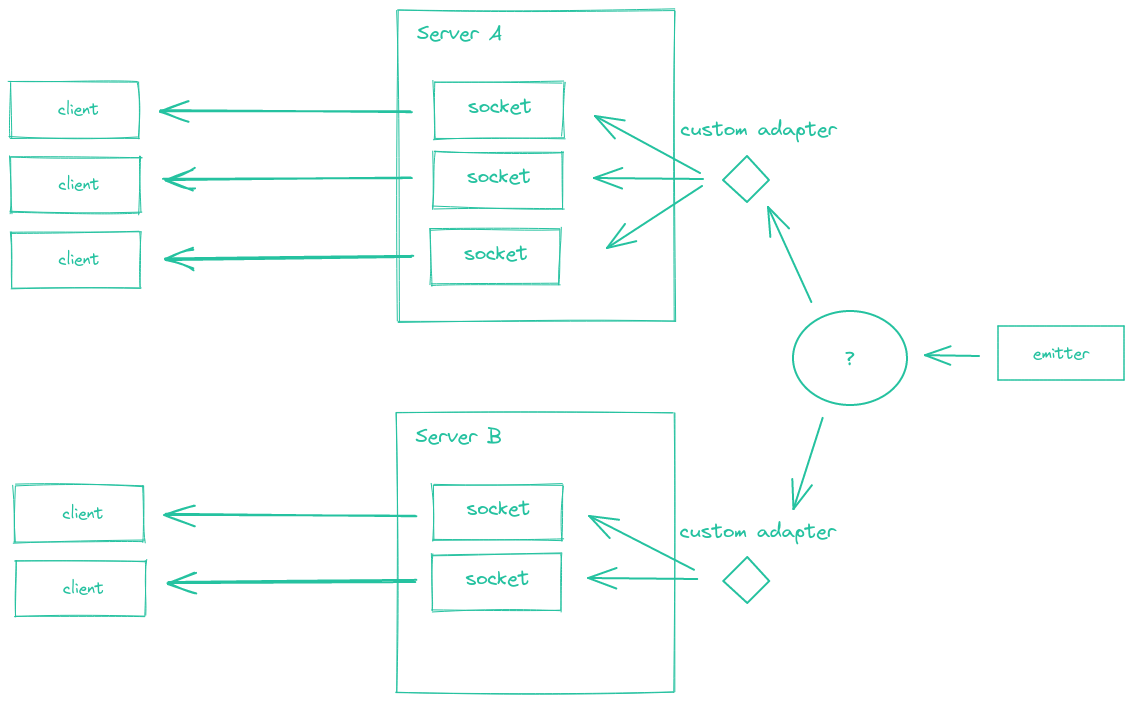

- Use the adapter pattern to notify multiple socket servers of a change across a swarm of running servers (The Event emitter here being the database proxy we discussed).

To account for multi-tenancy, given you don't have scaling limitations anymore, you can have a single cluster per paying user that auto-scales from one minimum instance and has isolation at the infra level, OR a full cluster of all your servers and a single database cluster logically separating your tenants. Depends on how critical and secure the data you store is supposed to be.

The creation of a complete auto-scaling realtime-database server "farm" is obviously out of the scope of this post, but it is an amazing case study in scalability and SAAS product building and distribution for engineers.